The Instruments of Praetorius’ Time – Part 2

By Ross Brownlee

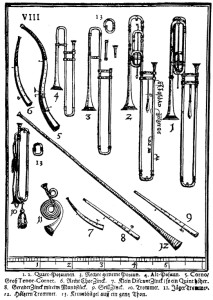

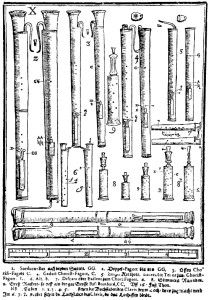

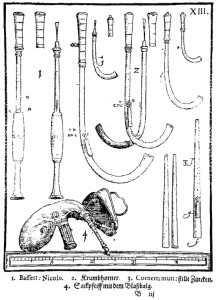

In Part 2, we explore more of the weird and wonderful instruments that Michael Praetorius (1571-1621) himself would have used and that will be part of the concert Praetorius Christmas Mass that we are presenting. The woodcuts that accompany this article were published in his book Syntagma musicum, published in 1619.

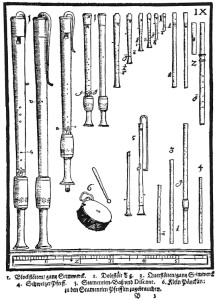

The crumhorn family.

Crumhorn – These curious instruments are another in the amazing wind section. Unlike the dulcian, shawm and rackett, these double reed instruments have their reed enclosed in a sealed “cap.” When the player blows at the top of the cap, the air chamber pressurizes and forces air through the reed, without it ever touching the player’s mouth. This makes for a very different kind of sound and tuning control! I have spent a week at Amherst Early Music trying to learn the crumhorn, and never have I experienced such intense pressure in my head! It takes amazing control to play these instruments, and enormous core strength to power them!

The shape is also very unique. Crumhorns are wooden and have a straight body, much a like a recorder. It is under the finger holes that they break away from the norm. The bottom of the instrument curves forward, away from the player, ultimately sending the sound soaring upward. Check it out on the Praetorius woodcuts! With a cylindrical body and no bell, the crumhorns also have a nasal, buzzing sound that is gorgeous and unique. Be sure to listen for their feature moment on verse 3 of In Dulci Jubilo!

Gut Strings – Our five wonderful string players have modified their instruments to play this performance. Rather than use their normal, steel core strings, our WSO players have removed the modern iteration and replaced them with strings made of spun gut. Yes! This is how all strings were made up until the advent of machinery that could spin steel into thread-like consistency! Poor animals! The difference in sound is remarkable and many people, upon hearing period performances have commented on the warm, earthy sound produced. This is due to the natural, gut core of the strings, and also from the style of bow and hand position used by the players to accommodate the natural strings. Why change to the steel strings in the 19th century? Mostly for projection. With large orchestras and newer, stronger brass, woodwinds and percussion, the orchestral strings had to play with a more potent sound to be heard. So, inventors learned to spin steel and make tighter, more powerful sounding strings. Here though, we will go back and hear the lovely and warm vocal quality of the original sound.

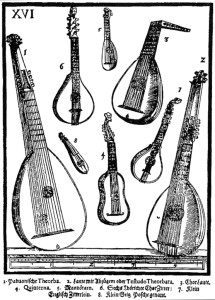

Theorbo and instruments of the guitar/lute family.

Theorbo – The original hybrid! This amazing instrument is half lute, the precursor of today’s guitar, and half bass lute, essentially a bass guitar. This was pure genius for the omnipresent continuo lines of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Rather than have a separate bass player, who would give the fundamental chord tone, and a high lute player, who would fill in the chord and rhythmic interest, by adding a long neck for the bass strings, one highly skilled musician could do it all! Theorbos were routinely paired with a small portative organ to fill out the chord structures to accompany singers and players alike.

This is another of my favourite instruments! It has a magical, almost other-worldly bass sound, unique to any instrument, but can strum and create rhythmic drive like any modern guitar! I often wonder why a modern version of this instrument hasn’t found more favour in today’s bands and singer-songwriters? The ability to play with such a wide range seems very appealing!

Recorders

Recorder – This beautiful instrument has been largely relegated to elementary music rooms in North America. But it is so much more! Like the cornetto, the Renaissance recorder is designed to allow skilled players tremendous virtuosity! Renaissance recorders have a larger bore diameter and larger whistle than the modern instruments, resulting in a rich, full, woody sound, ideally suited for singers and other period instruments. Listen for the soaring high notes of the sopranino, and notice the incredibly rich and gentle sounds of the larger tenor and bass instruments. The largest 8-foot recorders require a metal bocal to direct the players air to the top of the instrument.

Organ – The mighty organ at Westminster is the heart of this program! Such a marvel of engineering, the organ offers a range of sounds, dynamics, colours and combinations unrivalled in any other instrument! Using ranks of pipes, ranging from tiny flutes to mighty bass trombones (or shall we say sackbuts?), the organ can gently accompany a solo singer or instrument, or lead an entire audience of hearty singers! The skill required of the player is astounding. Not only must they be able to play the hand keyboards (there can be up to 5 of them!), but they must also operate the pedal board with their feet, change the ranks of different sounding pipes by adjusting the stops (controls for which type of pipe will sound), and spend hours beforehand, figuring which combinations of sounds and colours best suit the style and effect of the music they are playing. It is daunting and wonderful! Erik will adjust this Winnipeg organ to best recreate the colours that Praetorius, himself an organ builder, would have imagined for this wonderful Christmas Mass.